March 9, 2015

Currency wars: the US lost a battle but the war is not yet over

Commentary by Robert Balan, Senior Market Strategist

"Almost all the world’s currencies are dropping against the U.S. dollar. The decline is being driven mostly by governments and central banks bent on cheapening their currencies to gain an advantage in global trade and boost their weak economies. […] A stronger dollar makes U.S. imports cheaper, which forces domestic producers to stay competitive by lowering prices and laying off employees to cut costs. A rising buck, then, works against the Fed’s goal of price stability and full employment.”

Gary Shilling, Inside the Currency Wars, Bloomberg View, March 6th, 2015

Globally, we are seeing an almost concerted effort by central banks to launch economic reflation by pursuing a policy of lowering rates and/or injection of liquidity. The main impact of these policies operate through the depreciation of the local currency, and the ubiquity of the practice is contributing to the so-called “currency wars”. Major moves in the currency market affect growth; moreover, changes in the valuation of the US dollar relative to other currencies also have a major impact on commodity markets.

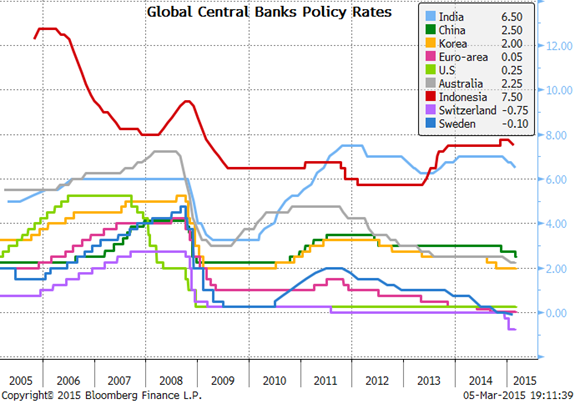

These past 7 years, central banks have implemented various strategies in order to support growth. Many benchmark rates have fallen to extremely low levels. The zero bound has proved to be no barrier — central banks have recently implemented negative rates in search for that "magic elixir" which could trigger an economic reflation. So far, the Eurozone, Denmark, Sweden and Switzerland have taken that route. Around $3 trillion of assets in Europe and Japan at maturities of up to 10 years have had negative interest rates in recent weeks (e.g., 10-year Swiss government bonds). For central banks unable or unwilling to go negative, there is also the Quantitative Easing route. And for those central banks that are at the brink of desperation, both negative interest rates and QE (e.g., the ECB) are seen as potent combination in launching a reflation process. The European Central Bank this month will begin a program of full-scale quantitative easing to match what the central banks of Japan, the UK, and the US have been doing for some years now. The People's Bank of China, by cutting its benchmark deposit and lending interest rates by 25 basis points last week, provided further evidence that global central banks are pulling out the stops in trying to reflate their economies.

With these easing policies, central banks are aiming to boost economic activity through two channels. The main and most obvious channel is the reduction in financing costs. Lower rates are also pushing investors into higher-yielding assets, while discouraging saving — hence encouraging consumption (see Commodities Insight Weekly, Commodities should benefit from the central banks’ race to the bottom, February 16th, 2015).

The second channel is the devaluation of the local currency. Sluggish trade growth has forced many central banks and governments into “currency wars” to maintain competitiveness. Not all countries can of course simultaneously weaken their currencies. Another currency has to be willing to take the other side of the foreign exchange trade — and for the past 6 quarters, that currency has been the US Dollar. This has caused the US Dollar to strengthen significantly. However, this has dire repercussions. A stronger dollar compounds the disinflationary impact from the drop in energy prices, and moreover also presents a significant deterrent for the US economy in general and the US export sector in particular. US consumer preferences are shifting toward cheaper imported goods, so US exporters are facing diminished demand due to a confluence of tepid external economic activity and reduced competitiveness on pricing. An example of this has been the decline in the US ISM new export orders, which sank deeper into contractionary territory (see charts of the week). This subcomponent is a useful leading indicator of exports in the GDP accounts, so it is a stark warning that the export sector is indeed foundering as a growth engine due to the strong dollar. Many US corporate heads have started to complain about the strength of the currency which has undercut their competitiveness. Even the Fed was thought to have given some consideration to the dollar's strength and the issue may have contributed to their stance to remain "patient" in raising the policy rates.

On the other side of the FX trade, many currencies have weakened (see charts of the week), especially in the Emerging economies, and therefore have succeeded, to varying degrees, in keeping their industries competitive. Since the beginning of 2014, major Asian countries have experienced a 4% to 15% decline in their currencies. These countries are typically extremely dependent on exports so a weak currency contributes significantly to their competitiveness, which in turn impacts positively on growth. Germany is also a beneficiary of the weaker euro after the series of steps the ECB has taken to try and juice the Eurozone's economy. The country's exports are booming after an 18% decline in the value of the euro. Stronger growth from these export-led economies collectively could have a positive impact on the demand for commodities.

However, the US Dollar's upside trajectory has been losing momentum as US economic data begin to falter, while the growth outlook for European and Asian economies have improved — thanks in large part to the central banks’ interventions. The growth differential between the US and the rest of the world could become a more important variable in the coming weeks as these economies adjust further to the new exchange rate levels and improved financial conditions.

This makes us believe that the US dollar may weaken soon, which would provide significant respite to the hard assets like commodities. We expect that by late May or early June, we should see global growth picking up as well even as US economic data stagnate. That should favor the commodities which are highly attuned to global economic conditions, especially the cyclical sectors like energy and the base metals. A dollar retreat should also benefit the agriculture sector which is very sensitive to the level of the dollar.

|

Commodities and Economic Highlights:

|

Commodities and Economic Highlights

Commentary by Alessandro Gelli

Declining rig count may underestimate the reduction in activity by oil companies

The 60% decline in oil prices between June 2014 and January 2015 has triggered adjustments from the supply-side. Oil companies are reducing spending, which should gradually translate into slower production growth and may lead to a decline in US crude oil production in the second half of the year. This anticipation is suggested by the 43% decline in US oil rig count since mid-October, and the major cut in capex announced recently by oil companies. According to RBC Capital Markets, 122 international energy companies should cut their capital expenditures by 20% in 2015. Some US oil companies have even announced larger reduction in spending. Independent oil and gas producer Apache Corporation announced a decline in capex of 60% from last year. This should contribute to significantly lower US crude oil production growth in the coming months, and according to the US government this should lead to a decline in US crude oil production from May 2015.

But some industry professionals think this may happen even sooner. Harold Hamm, the CEO of Continental Resources, the largest oil producer in North Dakota, thinks that US crude oil production could decline as early as April as US oil companies are not performing completions. According to him, about 85% of US wells are not being completed in order to reduce costs. Indeed, completion costs — mostly hydraulic fracturing — accounts typically for 60% of total drilling and completion costs, while in a conventional oil well the cost of drilling the hole (including casing and cementing) usually accounts for the bulk of all the cost. Oil companies have also contracts in place with drilling companies and cannot change them without paying large penalty fees, while it is easier to postpone hydraulic fracturing operations. According to the Wood Mackenzie and RBC Capital Markets, more than 3’000 wells in the key tight oil regions of North Dakota and Texas have been drilled but have not been completed.

Another reason to postpone completion is the low oil price environment. Tight oil wells have typically an elevated initial flow rate, followed by a sharp decline — in North Dakota, production at a tight oil well typically could fall by 65% after one year. Oil companies therefore prefer to wait for higher prices before performing completion as the bulk of the output will occur during the early part of the well’s life. The shape of the WTI forward curve is also suggesting higher oil prices in the future, encouraging oil producers to “store” crude oil in the ground. The contango on WTI allowed them to hedge future crude oil production at more elevated prices than spot prices.

This backlog of unfracked wells could reduce the likelihood of important oil price swings this year. Higher oil prices could trigger a wave of completions as oil companies make use of idle pressure pumping crews to perform hydraulic fracturing at unfracked oil wells. This could therefore lead to a relatively rapid rebound in crude oil production as it only takes 3 to 10 days to perform hydraulic fracturing. However, the situation is not as simple. The backlog of unfracked wells is not new. In June 2014, when oil prices stood above $100 per barrel, a significant amount of wells were waiting completions not because of low oil prices like now but because of the lack of fracturing crews. During the oil boom, drilling had indeed outpaced completions. For example, in June 2014, North Dakota had already 585 wells waiting for completion services; in December 2014, they rose to 750, accounting for 6% of total producing wells. Therefore, the recovery in US production may be constrained by the lack of fracturing crews. Oil companies may not be able to extract crude oil as fast as they want in case of higher oil prices, leading to wider price volatility.

Refined nickel should soon benefit from low Chinese laterite inventories

Last year, the Indonesian ban on nickel ore exports had a major impact on the nickel market. Without sufficient smelting capacity, Indonesia, the world’s largest producer of mined nickel in 2013 (accounting for 33% of global mined nickel output), was forced to reduce nickel production from 811’000 metric tons in 2013 to 144’000 metric tons (down 82% y/y). This indeed contributed to an almost 60% rise in nickel prices during the first 5 months of the year. The ban had an impact that was particularly important for the Chinese nickel pig iron (NPI) smelters as they use the laterite nickel ore (nickel content of 1% to 2.5%) from Indonesia. NPI is used by stainless-steel producers in China as a cheaper alternative to refined nickel.

But despite the Indonesian ban, Chinese smelters proved to be resilient as they have built high grade laterite nickel ore inventories (nickel content of 1.8% and above) ahead of the ban, which was anticipated by the industry. Chinese laterite inventories indeed rose at the end of 2013 to almost 19 million tons, a record high level. Since the implementation of the Indonesian ban, they have fallen by 34% to 12.5 million tonnes at the end of February 2015, the lowest level since May 2012. Moreover, Chinese smelters increased last year the use of nickel ore from the Philippines as a substitute to that from Indonesia. The Philippines managed to increase production and exported in the second half of last year on average 35% more nickel ore to China than in 2013. The low quality nickel ore from the Philippines was blended with the high grade nickel ore from Indonesia and have supported Chinese NPI production last year — albeit production gradually fell throughout the year. Nickel production in Myanmar also increased and should rise further this year. Nonetheless, the output levels are currently insignificant. Last year, mined nickel production in Myanmar reached almost 20’000 metric tons, while the Philippines produced 355’000 metric tons.

High grade nickel ore inventories have been declining sharply in China. Moreover, Philippines exports of nickel ore to China have slowed down due to the monsoon, and should gradually rise until July-August when they seasonally peak. They are hence likely to remain at a low level in the next two months, while the Chinese Lunar New Year holiday is over, implying a recovery in the economic activity. Weak Philippines’ nickel imports and relatively low Chinese inventories may reduce NPI production amid stronger seasonal demand for nickel, contributing to a tighter refined nickel market.

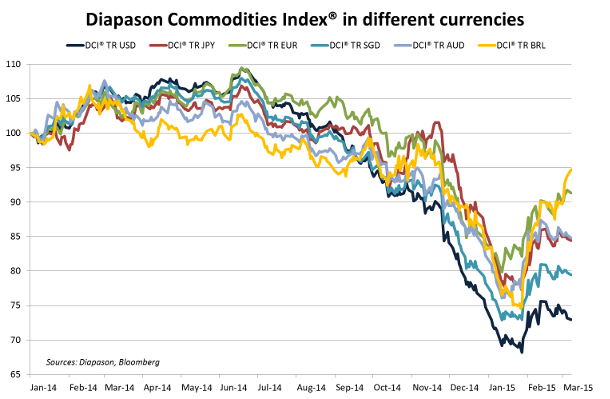

Charts of the week: Global Policy Rates / US Dollar vs Exports / DCI in different currencies

|

Global central banks are cutting policy rates in order to boost economic growth. The recent cut in rates outside the US, while the Fed is talking about the possibility of a rate hike this year has contributed to a significant appreciation of the US Dollar — while pushing down the value of other currencies. This has started to affect export-oriented industries in the US, which in turn could lead to lower economic growth in the US. |

|

|

For the full version of the Diapason Commodities and Markets Focus report, please contact info@diapason-cm.com

.png)